Learning about rural education and sustainable development -Valeria Ramírez Ensastiga, MA NCSS ‘21

During these two weeks collaborating with The Hunger Project- Mexico (THP) I have had many learnings and reflections although I also have felt that time has passed incredibly fast. I would like to start by explaining how, due to the health contingency, the initial proposal to carry out this fellowship was modified, and then tell about my experience of these first weeks.

THP works to eradicate the systemic causes that generate most of the conditions of poverty in rural and indigenous communities as well as to generate development and better living conditions while at the same time trying to respect their own idiosyncrasy and the natural ecosystem that surrounds them. Therefore, the initial idea of my participation was to visit the communities and develop visual material to help the dissemination of eco-technologies in which some residents have already been trained, as well as the promotion of other sustainable practices that can provide these towns and communities with more dignified living conditions and help them build resilience to the threats caused by climate change.

Since the current health contingency does not allow to carry out face-to-face activities and contact with the communities is extremely complex because there isn’t a stable internet connection or reliable telephone networks, the proposal moved towards creating educational material about sustainable development for children with the objective of it being used, in the near future, more widely within various rural schools. Informing children about sustainable development, and how it relates to their rights, is vital to create in them a cultural citizenship that empowers and allows them to participate in the construction of their communities. Perhaps to the reader, this last line might sound too radical, but the more I investigate, the more aware I become that these children grow up immersed in an environment that constantly tells them to resign to living in deplorable conditions while also stealing any aspiration to escape the systemic violence that places them in extreme poverty and environmental inequity.

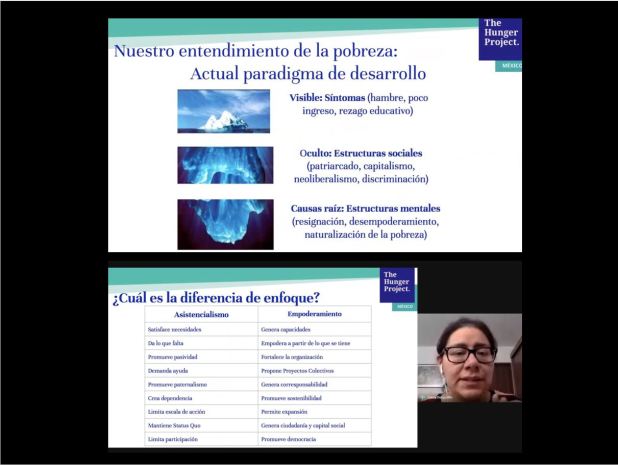

During the first days, I learned about THP’s working methodology and understood some of the guidelines my proposals should follow so that they correspond to the values and vision promoted by the organization. THP starts from seeing people in poverty as the greatest experts in knowing what changes are necessary to eradicate the causes that generate the situation they are living in. They also seek to develop their potential to be agents of their own transformation instead of requiring them to wait for external assistance.

Later, I started researching and understanding, on the one hand, what materials could be available to explain sustainable development to children and, on the other, rurality, and in more detail rural and indigenous education. In the beginning, I felt a little sad about not being able to visit rural communities, but I also was worried about developing educational material for children who live in a different reality from mine and other children with whom I have previously worked with in highly urbanized populations. Dear reader, please notice that I was born and raised in Mexico City, one of the most populous cities on the planet. Thus, it was necessary to look for alternative ways of doing my ‘field’ documentation.

First, I read carefully about the characteristics of the rural education in Mexico and Latin America, and I found that, unfortunately, although there is a lot of talk about the need to improve rural education there is very little educational material designed specifically for this type of schooling system. Rurality in this context does not only refer to the fact that people live in places far away from large cities, or that most of the economic activities are related to agriculture and livestock but unfortunately, most of these communities lack basic infrastructure, sometimes electricity, sanitation, roads and even tap water. So talking about sustainable development to children living in these conditions, of course, cannot follow the discourse that has spread widely to the most privileged classes, either academically or economically. On the other hand, rural education in Mexico is usually multilevel, that is, a single teacher teaches classes for two or more levels. It also occurs that a single teacher cares for a group of up to 40 children from 5 to 12 years in a large classroom. In addition, many of these communities are indigenous and Spanish is not the native language of children, but it is the language in which the official educational texts and working tools provided to teachers is written in.

Diana, Manager of Alliances and Advocacy in Public Policies at THP was very kind to share with me some previous experiences with the communities. She also provided me with some reports of activities, led by THP or other partner organizations, related to the environmental education that has been carried out within the member communities. Some examples of the topics that have been worked within these communities are caring for water; reducing energy expenditure; and separating solid waste among others. Thanks to this information, I understood more clearly what kind of actions the material I will develop should invite the community to do. I also find it very interesting to see how the small size of these member communities where everyone knows each other, could possibly allow the proposal of community actions that have a big impact in the long term.

Besides, I also searched online the existing educational material regarding sustainable development specifically designed for children, having special attention in finding content developed for the Global South. It was alarming to see that the dissemination material is highly oriented to the privileged classes. There is practically no material on the actions that underprivileged children can take or demand to achieve sustainable development worldwide. The UN 2030 agenda points out the goals on which it is necessary to work, and there is a lot of academic information on how all social groups are capable and have the right to collaborate on achieving them. However, I noticed that such information is not being widely disseminated nor it is adapted to different contexts. For example, one action that UNICEF suggests that children and young people can carry out to achieve the proposed Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is to “place carpets and lower the thermostat temperature to save electrical energy”. However, saying that to a child from a rural community in Mexico would be totally out of context. Of course, those recommendations are valuable to some populations but we need to be more inclusive and generate diverse content for different audiences. Therefore, after going through some discomfort due to this finding, I concluded that the material I will try to develop, thanks to the Maharam Fellowship, may seem like a drop in the ocean, but it certainly can become a very valuable contribution.

Working on this project excites me, but at the same time, makes me feel a great responsibility. So, this first part of my internship has been dedicated to performing careful research, which now I believe is very important for achieving successful results, first, in terms of the reception it will have, but especially in terms of the impact it will have on the children and teachers who at some point will have this material in their hands. For this reason, I also have decided to approach former friends and colleagues who have worked in rural communities in Yucatán and others who have worked on environmental issues with children to get feedback. They all recommended developing a deliverable in a simple language and that I should not worry about including all the necessary topics, but instead that I should explain carefully the topics I consider to be the most essential.

Lastly, this educational material should serve both children and teachers. Therefore, it’s relevant to understand how the teacher can introduce it to the children and what is the easiest way for him/her to achieve his/her goals while also sharing all the valuable information contained in the material to the pupils. However, I also feel that I have some valuable experience that might allow me to achieve this goal. A few years ago I worked as an instructor in a school garden within the Montessori methodology and I remembered that, during the process of learning to teach, I must observe other teachers working with children. So, imagining a similar exercise, I watched the documentary “The Sower” by Melissa Elizondo, which is a story that narrates the daily life of a rural teacher in Chiapas (one of the states where the material I’m developing will arrive). It is admirable to note all the effort and dedication ‘Teacher Bartolomé’ has to encourage children to learn and to take care of themselves and others while respecting their identities. Watching this documentary has inspired me to carry out this work with a lot of affection even within the confinement of my desk.