Into Their Culture, Helina He Yuheng, BFA ID 2023

Into Their Culture

I was out of quarantine. I was excited since I was finally able to enjoy the other half of my program in person. On the same day, I drove non-stop from Chengdu to Sêrtar County, to find Zhou Ba, the coordinator of LDONGTSOG. Sêrtar County is remotely located on the border of Qinghai Province and Sichuan Province, with an altitude of around 4,100 meters above sea level. However, Sêrtar is still a five-hour drive away from Kehe Village, where the base of LDONGTSOG is.

from Baidu Map

In the following two weeks, I will be living with Zhou and his family. I will make use of this chance to observe their lives and learn some Tibetan language. Thanks to the seminars I held, I already had a basic understanding of the culture that I was going to enter: their religion, their history, their customs, etc.

On the night that I arrived, I was welcomed with a cleaning ritual by Zhou Ba and his wife Mu.

Tibetans believe the smoke of birth leaves can clean away the dirt.

As a gift of exchange, I brought them the book Everest from the United States. It is illustrated by Lisk Feng, a former professor at RISD.

Two days later, Zhou Ba took me to the Sertar Larung Five Science Buddhist Academy (色达五明佛学院,གསེར་རྟ་བླ་རུང་ལྔ་རིག་ནང་བསྟན་སློབ་གླིང་). The main entrance is closed for outcomers due to COVID, so Zhou Ba guided me to bypass the examination spot by climbing the hill. What an unusual way to greet this splendid architectural complex!

After we climbed over the hill, I saw thousands of red wooden huts packed in the valley. According to unofficial data, the academy grew to 20,000 students, despite the government’s efforts to reduce the number in recent years. I saw Buddhist temples with gilded roofs amidst the red ocean, flashing against the sunshine. Monks and nuns walked about in maroon robes, chattering in Mandarin and Tibetan.

It was only then that I realized when I was visiting the largest Tibetan Buddhist institute in the world.

The Buddhist academy is modernized though. I bought Zhou Ba a cafe chat, and asked him some questions about LDONGTSOG. He shared both his expectations of me and the difficulties that LDONGTSOG has faced. During the conversation, I saw Zhou’s deep compassion on animals and the environment.

I was grateful that Zhou Ba took me to this Buddhist Academy when I first came to Sertar. Because it wasn’t until I visited here that I realized the importance of Tibetan Buddhism to the locals. Only with sincere religious beliefs can Tibetans build a school spanning across the valley in just 40 years.

Suddenly, the argument I mentioned in my last post has its reason: the best way to educate traditional Tibetans about the environment is through religion.

Then Go to Their Nature

One week later, I begged Zhou Ba to take me to the forest at Kehe Village. As Dr. Losang Rabgey, the founder of a Tibetan cultural NGO, advised me, “Your design will be different even if you breathed the air in Tibet.” I wanted to see the vegetation, animals, and cultural life of LDONGTSOG in person.

I met other group members of LDONGTSOG at the village. They took me to the primeval forest. The forest was a place signified by its biodiversity. At the foot of the mountain, it was the typical scene of a temperate monsoon climate. Tall trees and wild strawberries were visible. The landscape transformed into rocks and grass resembling those on a plateau as we ascended the mountain. At the top, we held a worship ritual for the mountain god Dongge. Zhou Ba said it always rained after the ritual was performed.

At night, I saw the most brilliant starry night I have ever seen in China. I used to believe that city pollution had caused the stars to fade, but now I see that they still shine where there is nature. Protecting this pristine region from the consequences of human civilization became spontaneous for me.

What’s next?

LDONGTSOG is going to host an eco-trip in August. I intend to write some instructions for the tourists coming to Kehe. Additionally, I will design pamphlets and maps that tell the story of LDONGTSOG. I am driven to use my writing and design so that visitors to Kehe will value the local nature and culture just as much as I do.

Seminar as Method, Helina Yuheng He, BFA ID 2023

Week 2-4: hosting online seminars

Hello.

This summer, I am exploring different innovative techniques to help sustain a grassroot Sino-Tibetan environmental group, LDONGTSOG, located in Kehe village, Sichuan. Public education is one of my main focuses.

I once asked a volunteer from LDONGTSOG for her advice on entering the Tibetan community. She answered, acknowledging two different cultures and keeping your gesture low are the key. Keeping the gestures low, I invite you, dear audience, to do the same with me. To set aside all existing judgments, because “environmental protection,” “Tibetans,” “indigenous people,” and “nonprofits’’… these concepts are not equivalent in PCR discourses as they are in the US.

Towards the end of the Spring semester, I attended a dinner at RISD to discuss community engagement. At dinner, one of the students talked about her idea when one enters a community that he or she is not familiar with. That is not doing “research for them” but doing “research with them“. Following that, I contemplated the implications.

To “research with them” means making it clear to my research subjects that the research will have an impact on both sides, rather than hiding my purpose from the subjects. Taking this notion in mind, I came up with the idea of holding a public online seminar targeted at Chinese youth. This seminar fulfills two purposes: 1. For the Sino-Tibetan community, it is to highlight the efforts of Tibetans (such as LDONGTSOG), who have always been underrepresented in the mainstream, creating a shared space to help people understand them; 2. For me, as the researcher, it is to widen my research scope and to learn more about their culture.

Seminar as Method

From July 10th-July 24th, I have been hosting public online seminars related to the Tibetan environment and its cultural heritage. My guest speakers include normal travelers, environmentalists, anthropologists, artists, and educators. My starting point was intuitive and simple: to let more people know about the Sichuan-Tibetan nature and culture, represented by LDONGTSOG, the organization I am helping. Nevertheless, the seminar has been developed to a level that I never imagined before. I personally gained friendship and trust through the seminars. And new ideas burst out of the process.

I became the host, the organizer, the communicator, and the designer of my seminars, which left me a ton of work. Thankfully, I have found three other friends who are willing to collaborate and help. We all share the same interest in Chinese ethnic knowledge and mythology. They are: Yiwei Chen (INTAR ‘22), Chenxi Wang (Ceramics ‘23), and Yiqing Lei (Sculpture ‘23). They helped me organize meeting notes and host the panels.

It is through hosting seminars did I realize that it can be an anthropological research method. I titled it, “Seminar as Method”. This notion is borrowed from Xiang Biao (向飙), the Chinese academic celebrity in social anthropology. He published a book called Self as Method in 2020, and tells Chinese youths “to think for themselves and through their own experiences in making sense of the contradictions around them” as if doing scholarly research1. Xiang’s idea inspired me to look at the medium of online seminars, which grew popular thanks to covid. The online seminar has become a medium for me to approach and observe my research subject.

I have found seminars a way to bond communities together, which suits the principle of “Research with them”. On the one hand, holding seminars spreads the influence of my guest speakers, who share an affinity with the Tibetan community in China. On the other hand, hosting seminars forces me to absorb knowledge in a short amount of time. By hosting the first two events (the last seminar will be happening soon), I felt such a sense of satisfaction by doing things for the Tibetan group. Also, I gained general trust from the Sino-Tibetan community and made new friends, since they saw my efforts and respect for their culture.

Holding seminars is different from holding personal interviews. In one-on-one interviews, I post questions for myself, and the only audience at that moment is the interviewer. By contrast, the seminar is a performance for the audience, and I play the role of the host. In this case, I do not ask questions for myself but for the audience. Thus, the seminar has created a safe space to ask critical questions that seem embarrassing to post during interviews. The guest speakers answer questions in a more articulate and informative way. Besides, I can ask guest speakers to make in-depth presentations for the audience, which will be hard to request in one-on-one interviews.

It is through these seminars that I gained a deeper understanding of not only LDONGTSOG, but also the relationship between nature and the culture in Tibet.

Takeaways from the First Two Seminars:

the Twinning Relationship between Nature and Culture

As I mentioned before, it is through my seminars that I understand what LDONGTSOG(玛荣峒格) really is. LDONGTSOG is a grassroots organization located in Kehe Village (柯河村). Kehe(柯河) is the name given by the PCR after the cultural revolution. However, all elderly Tibetans refer to it as Dmar-rong (玛荣, དམར་རོང་), which is where the first two characters of its name, LDONGTSOG, originate. Dmar-rong is its own center, its own world before it is called Kehe Village. Dmar-rong’s relatively remote location has allowed Bon (བོན), the indegenous Tibetan religion, to grow there.

In my opinion, Dmar-rong has one of the most breath-taking natural views. However, this hidden gem is under threat at any time. The government is building a new road, which produces slope debris flow. Debris flow reflects the surface problems; the disease of local animals reveals the rooted illness in the environment. This results in Zhou Ba, the founder of LDONGTSOG, approaching the moss disease of local animals. The approaches that LDONGTSOG took include making documentaries, building the botanical garden, and educating local citizens.

During the seminars, I asked Zhou Ba, “Why do you focus on cultural protection if LDONGTSOG is an environmental protection organization?”. Then I realized that the traditional Tibetan culture provides a deep insight into how humans interact with nature. In fact, the most efficient way to educate environmental protection in Tibet is not through scientific data but through lamas’ lectures2. It is the religion that supports Tibetan environmentalists like Zhou Ba to insist on their causes.

In my first seminar, I interviewed a Chinese theater student as well as an avid hiker called Zhuo Xue. Xue has been teaching Shakespeare in China since he graduated from Oberlin College. He attempted to combine culture with nature. In 2019, he has organized a hiking event in Yunnan Tibet with Chaofan Han. They hiked in the daytime and read Shakespeare in the evening. After that, he entered Tibet several times, and he was mentally surprised by the Tibetan worshippers along the way.

Xue argued in his lecture that Tibet is one of his favorite sites so far. Unlike the modern-day practice that separates nature from society manually, the nature in Tibet is its culture. Sacred mountain gods live in the caves and on the cliffs. Because of the belief, the Tibetans put prayer flags in even the most dangerous spots in the yard, summoning their respects to their nature gods. Xue’s lecture showed that living in harmony with nature has been an integral part of Tibetan Buddhism. The present-day global concerns for sustainable development and conservation of natural resources are suggested by traditional values in Tibet.

Thanks to the first two lectures, I decided to look into the traditional values and practices of Kehe Tibetans. Because culture plays a big supporting role in Tibetan environmental protection. A path to civic engagement is opening up in front of me…

Helina

Footnotes:

- David Ownby, Xiang Biao, Excerpts from Self as Method, Reading the China Dream. https://www.readingthechinadream.com/xiang-biao-excerpts-from-self-as-method.html#:~:text=Self%20as%20Method%20essentially%20tells,how%20one%20scholar%20did%20so.

- See 《守山:我与白马雪山的三十五年》, 肖林 & 王蕾, 北京联合出版公司, 2019。 Xiao, Lin & Wang, Lei. Guarding the Mountain: My thirty-five years with Baima Snow Mountain. Beijing United Publishing Company, 2019. Xiao is one of the first environmentalists in China. In this book, he demonstrates his life-long practices of environmental education as a Tibetan.

- S.M. Nair, Cultural Traditions of Nature Consevation in India, http://ccrtindia.gov.in/readingroom/nscd/ch/ch11.php

Shifting to Online Engagement, Helina Yuheng He, BFA ID, 2023

First week: defining and grouping

Hello, dear friends.

Welcome to the first week of my journey. If you are reading this post, then I am fortunate to have you witnessing my project to protect the Sino-Tibetan environment with public education and design thinking.

My name is Yuheng (Helina), and I am a senior in Industrial Design with a minor in Art History and Theory. I was born and raised in an ethnically multicultural area in China (Guizhou province), and therefore, I naturally sought to help and protect a minority culture (the Tibetan culture in Sichuan) when I decided to apply for the Maharam fellowship.

Many of you might ask: who are the Tibetans? And why are they significant to the environment as well as the cultural landscape in China? Well, let me throw in some explanations so that it will be easier for you to follow my upcoming updates.

The Tibetan people are spread across different countries. In China, the Tibetan area is located in the west, extending over four provinces of the country—Qinghai, Sichuan, Gansu, and Yunan. They have their own language (Tibetan) and religious tradition (Tibetan Buddhism) that are different from Han Chinese (the majority Chinese ethnic group). The Tibetan environmental group that I am helping sits in Sichuan province, the one of the four that has most frequent communications with Han Chinese.

Located in the Himalayas, Tibet holds the highest mountain peaks and the most extreme cold weathers. It is dubbed the “pure land”, attracting numerous tourists, hikers, and naturalists every year to witness the breathtaking beauty of the area. Besides, any pollutions to the land will be directly reflected on the mountains and rivers in Tibet.

The environment in Tibet is facing danger due to industrialization. The snow line of the mountains has been rising. Poachers also appear around the forests in Tibet to steal animal skins and fish. In response to this crisis, many individuals and grassroot organizations have stood up. One of them is the organization I’m working with, LDONGTSOG (Chinese: 玛嵘峒格). It is located at Kehe Village, Aba County, in Sichuan province. Organized by a previous Tibetan monk, LDONGTSOG employs Buddhism concepts1 to educate local people as well as poachers. LDONGTSOG is a very small-scale organization based on local villagers. They accepted my help this time because they wanted to extend their influence beyond the village level, reaching out to youths in the city. With my Maharam fellowship, I want to bridge the conceptually “marginalized” Tibetan group with Han Chinese people and convey their organization’s value through visual means.

Unexpected Challenges

Although the idea seems charming, my plan was messed up by the sudden COVID outbreaks in China. The government tightened the border and required people from abroad to be quarantined for around a month (update: 2022/6/20) before they could move freely.

I was hesitant to go back to China due to these restrictions. Is it worth traveling for? What will I face when I return home and live in their village? Finally, I decided to seize the chance and embrace the uncertainty that this journey would bring.

The COVID outbreaks also means that I have to change my initial plan, which was to spend my first two weeks with the villagers and learn the culture before doing any design work. Obviously, it will not work out, and I will have to be remote for the first couple of weeks. Tibet is so unique that I do not want to make any assumptions about it before actually doing fieldwork there in person. My teacher once told me, “You will design differently once you breathe the air in Tibet.” I do not want to rush.

So, I stepped back and asked myself, “What is my goal in this journey?”

“To define a strategy of environmental protection derived from Kehe villagers’ unique perception of nature.” I answered.

“To connect people from outside and inside, sharing Tibetan’s holistic approach to nature with city inhabitants.”

“To unwrap my design process as an art historian student and designer, and honestly record Tibetan folk cultures in relationship with their environmental protection.”

Paths

With the answer in mind, I decided to shift my focus to online engagement with Chinese youths for my weeks in quarantine. My first and foremost task is to back up my knowledge of Tibetan culture by connecting to other professionals, since I have limited insights at this point.

The first organization I connected with is called Machik, which built the first K-12 school using Tibetan as the major instruction language in Litang County, China. Their founder, Dr. Lobsang Rabgey, was so kind that she offered me a free language lesson.

Then, I traveled to Philadelphia to meet another Chinese scholar in Linguistic Anthropology who researched environmentalism in Sichuan-Tibet. She provided me with information about other environmental activists in Tibet and inspired me to not measure the Tibetans and their culture against the western standard of environmental protection. She also emphasized the importance of fieldwork, which she believes is the best way to pay respect and attention to ethnic culture.

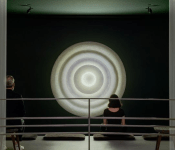

I also visited the Robin Museum of Art in New York. And I was delighted to discover how Tibetan knowledge and tradition were continued and transformed into contemporary visual languages.

After the initial research, I found that so many Tibetan young adults and residents doing social innovation works related to cultural and environmental preservation. The current issue is that these social innovation organizations are usually localized and fragmented.

One Approach

Then it raises the question of how to create civic engagement effectively? I know that many Chinese university students have endless curiosity to the unique environment and culture in Sino Tibet, so I decided to make them as my major audience group in my online campaign.

My following days in quarantine will be dedicated in the planning of online forums targeted at Chinese international students and scholars aged 20–30. I reached out to one of the biggest community-based youth organizations in China named 706 (https://706ny.com/706). I will use their platform to produce 2-3 live broadcasts in communication with outstanding youths and groups that have engaged with the Tibetan environment or culture.

This diagram serves as my road map for the forum. Currently, I am in the phase of outreaching to speakers. I believe this forum is a great opportunity for me to learn more about the Tibetan community that I will enter, and for other Han Chinese students as the first door step to connect Tibetan Chinese.

This is my report for today. Please keep an eye out for the upcoming posts if you are curious how the online forums will develop.

Thanks!

Helina

You must be logged in to post a comment.